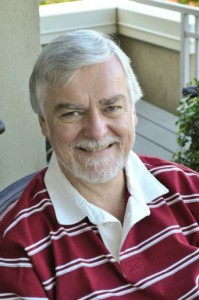

My dad, Bryan Hayday, died last week. This was my eulogy at his funeral yesterday.

(I swear, I wrote the first part before the hall’s amp system failed).

:::::::::::::::::::

When I was working with dad on a big meeting, we’d always discuss the requirements (AV, projectors, room layout) — he had an affinity for (and ability to do math on) table configurations that was beyond me (“so we’ll do 8 round tables of 6 and if 3-4people don’t make it in time for the start, we’ll move these two over here and have 5 tables of 5 and one of 2…”). The math part of dad’s brain was terrifying. He’d say “I’ll be there in 7 and a half minutes” and. he. was.

But when they asked about the mic for a big meeting, he’d only insist on one if the room was approximately the size of a basketball court. Otherwise it was “pffft, 80-90 people? I don’t need a mic”. And you could always hear him in the cheap seats.

Which, as a somewhat shy child, I actually found a bit mortifying, standing beside him at St Gabes BELTING OUT the songs. It was hard, especially since, as a budding atheist, I was really just there for the cookies in the basement afterwards.

I could try and wax eloquently about death — wax on, wax off. The piece that strikes me is that it is life’s big non-negotiable. It just is. When you get the call that someone has died, you can’t ask to sit by their bed and hold their hand. No one “pulls through” death. They’re just gone. Which is so strange, because we’re all so different. Everyone is so unique. It’s so unfair and bizarre that they can just suddenly not be here anymore. They just Are Not Anymore. And you don’t get a new one. That mash of cells and ideas and reactions and beliefs and history and thoughts has just rung down the curtain. They have ceased to be.

In my dad’s case, I feel like I was given a gift of extra time. With a big scare last year, the possibility that he would not come back to me/us became very very real. And it gave us a chance to think about all those things that so often are just suddenly snatched away. We had a chance to love him and let him know that we loved him in that really up front, clear and present (Sean Connery shout out, Dad) way — not just in a eulogy at a funeral where he can’t hear how awesome I think he is.

Because we worked together, I would often try and keep a separation between church and state. So emails from me usually looked like: “Please find attached the latest version of the report … vis a vis… ipso facto”. And then I’d get a response from him. That looked like: “Hey road warrior, Looks great! Also – do you want to add on a quick coffee to our Goodwill run? Tell your husband that I said to rock on. love, Da.”

He was always signing work emails “love”. And it drove me crazy. But especially after his surgery last year, I started feeling like “gah. Well it’s not that I don’t love you. Aw goddammit it. “Please find attached blah blah blah LOVE Catherine”.

What is hardest about this, I don’t think will ever get any easier, is that he was not ready to go. It was the complete opposite. He was just getting started. He was going to face the biggest challenge of a young workaholic’s life, the big R: Retirement.

But he did love his work, which is pretty extraordinary, and I loved working with him. Even though working with a morning person can be great, he loved using video chat. Which meant that I’d barely have sat down at my computer with cup of coffee #1 in what were essentially pyjamas, when the little gmail video chat dingle would start going off. And then pop and “helllooooo!” And because he had 2 hours headstart on me, he’d get away with doing distracting things to entertain himself while I was quickly skimming a document he’d just sent me… like staging elaborate pantomimes involving finger puppet rabbits… and maybe scissors. The man had a dark sense of humour.

For the first few days after his death, there were all these creepy digital echoes of him. Like, his gmail stayed logged in. So he was sitting there, with a “busy” status, and an away message of “Northern Ontario, yup”.

But I was thinking about it, when the two of us were online at 5am the day after he died, and I think, given that aforementioned exceptionally dark sense of humour, he would have thought it was funny. Specifically, if I could tell him about it, I think I know what he would have said. And what he would have said was “…boo.”

And then I’d say “Dad, that’s not funny.” And he would say sorry. And then, if he could, he would quietly change his status to (quotes) “boo”.

(Some of this is about how my dad was a little bit evil, and I am the apple off that tree.)

I mean, Bryan would just lie to you. For sport. Fortunately, he also had approximately one gabillion “tells”. There was one that was sort of a pause, and there was one where he started a sentence with “Actually…”. I got so good at them that I could head them off, I’d be like “no. stop it. I know what you’re doing.” and he’d be like “oh come on, I don’t even get to do it?” and I’d be like “… sigh, fine” and then he’d launch into a story about how Timbits were “actually” named after how Tim Horton used to have so many of his teeth knocked out in hockey that they’d call them Timbits… etc.

Or when I would phone him after his heart surgery, almost unfailingly he would answer the phone with this very wobbly weak STAGED “.. heeeellllooooo? Kaaate? is that you? I’m so old and feeble”. Between his love of yarn-spinning, and his terrible terrible terrible impressions which somehow always faded into an Irish priest accent: The man was a ham.

That ham gave me a huge gift I keep thinking of (and I love that he knows I’d roll my eyes at having to use the word “gift”). It’s something I’m only just beginning to appreciate and understand. My dad was proud of me. Of all his kids. Without hesitation. My whole life. To know, completely, that your dad is proud of you, not because of a tangible (a report card, or an ability to drink ungodly quantities of scotch (*fistbump to dad*)) or because of a specific accomplishment (though holy crap how he loved those), but because he is proud of who you are, or who you are becoming, as a person. Sometimes he would even “come around” and be proud of you years later for a decision you made that he initially disagreed with. To be encouraged. To have someone in your corner. Who thinks just about everything you do is just great, or “way cool”. And who lets you know that? All the time? Clearly and articulately? It is literally the best foundation a dad can give you.

A dad who was loved by a whole lot of people. From age 12 up through early last week, people I’d never met were always coming up to me and saying “oh! Hayday?! you’re bryan hayday’s daughter!”. I’ve been “Oh you’re Bryan Hayday’s daughter” (all one word) almost my whole life.

People who knew dad 20 years ago would launch into very specific things that he taught them. And I would be “ooookay, that’s nice. De Bono’s hats you say?”. But in the last few years, I began to really mean it. To really appreciate that I was proud of him.

Not “him” dad, but “him” Bryan. As he and I were just hitting that place where you’re starting to understand each other as people. His parents didn’t give him that many life tools. And he just figured it out. Bootstrap doesn’t even cover it. First he found a cow, then the cow became leather, then the leather became boots, and straps, then he attached them together… He worked really really hard, and he built this life for himself that he loved. All on his own. He came. so. far.

And still he did that while putting every. single. person. ahead of himself. But ironically while always encouraging other people to think about what they needed, and where they wanted to go.

He was very open, and so important over so many years to so many people. But there was also a very small piece of him that he told me about once, and that I was beginning to understand, that he kept for himself, that was very very private. In this person who shared almost everything of themselves, he kept this very small piece that was just for him, and that was aside, and that I don’t think any of us knew.

It’s true that after someone dies, people hardly ever call you to say “man, that guy, what. a. jerk.” But I think maybe because people were always going out of their way to compliment dad (directly, or via us) in life, that the overwhelming outpouring of memories and love feel so incredibly genuine. I think that dad’s genuineness and unbridled, determined positivity was infectious. And when people say “he taught me 20 years ago and it meant so much” or “we loved working with him” it feels so true. There are people who remember collating reports with my dad as being an insightful and life-changing experience.

And he would want you each to know that you were also important to him. That he loved you all back.

I can already see some of the places where it will be difficult for me to see echos of him.

Because it was a huge spring ritual to have dad adjust your bike seat (not a complicated bit of mechanics, and this from the man who would now say that he was a “credit card and duct tape home owner”), I think it’ll always be hard for me to ride down the Lakeshore and see grey-haired men out for a ride. (And there are a lot of them.) And every time I flip over a toe cage on my pedals, because dad had a toe cage because he had an adult bike.

And gelato and driving and tennis and certain kinds of sneakers and scotch and sweaters and cars and green jackets and scotland yard and goodwill and dancing and basketball and coffee that is 90% milk and 10% coffee. But, like I was saying to my cousin, when we were trying to make sense of this, I said that to be reminded of someone you love, right afterwards, it’s painful or at least it gives you a moment of deep sadness. But as that starts to heal, isn’t it actually really nice? To be frequently, intermittently, tiny-ly reminded all the time of someone you love — that’s not a bad thing.

Just one more of those tiny memories:

We were once playing Battleship, and I was getting so frustrated because I couldn’t find him. And I kept calling out locations all over the board, getting increasingly agitated. Until I finally realized about 10 turns later that every time he made a guess, it was the same coordinates (“E8” “Huh, how about E8?” “Let’s try… E8.”). For 5 minutes. The location of his boat.

Note: This is not a childhood memory. (This happened recently).

The fact that he is gone is stupid and unfair. How often already I think “oh! I want to tell dad about that!”. I’m in the habit of thinking that a dozen times every day, and now each time it stings. If he was here, he would say “Go on, it’s okay. You can be mad at me that I’m gone. I’m mad that I’m gone. But I love you.” And even though his physical heart was weak and lousy and gave out way too soon, his loving heart was unboundable and he spent his whole life stretching and extending it, and I find I’m incredibly glad that it extended so far and enveloped so many people.

If it is painful for you to remember him right now, please also remember that he would be very understanding of tears, but he would want laughter and smiles and maybe a Monty Python joke or two.

So please, carry him with you. I know that I’m very proud that for the rest of my life, I will be bryanhayday’sdaughter.

Thank you.